Kit Houses

Kit Houses

The Time is Right

Kit Houses and Twentieth-Century Innovation

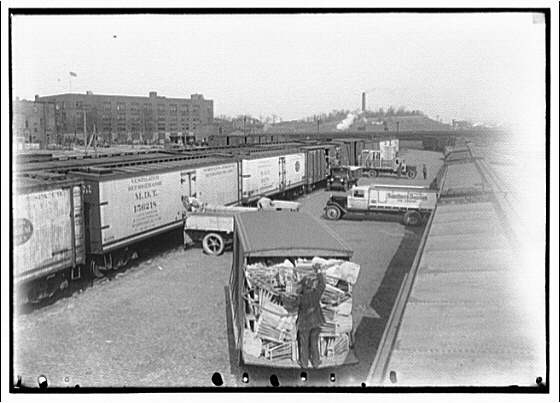

The story of twentieth-century architecture begins with late nineteenth-century advances. The Second Industrial Revolution (1870-1914) brought innovation to nearly every sector—manufacturing, transportation, construction, communications, and media. Ideas and products spread rapidly across the country, and a growing middle class eagerly embraced them. Thanks to the standardization of parts and assembly-line production, goods became less expensive to produce—and therefore to buy. An expanding railroad network, which stretched coast-to-coast by 1915, supported a national market for raw materials and finished goods.

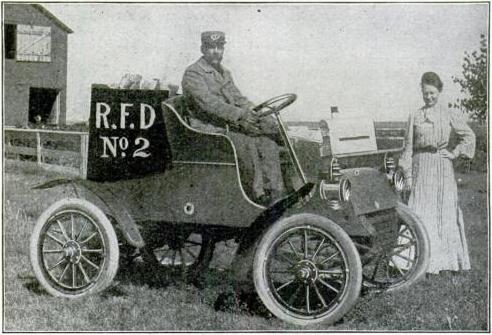

By the early 1900s, universal mail delivery began to open untapped markets. Implementation of Rural Free Delivery, established by legislation in 1896, initially stalled as local retailers pushed back, fearful of competition from large catalog retailers like Montgomery Ward and Sears, Roebuck & Company. The two catalog behemoths had been delivering their encyclopedic catalogs to urban households since the late 1800s.

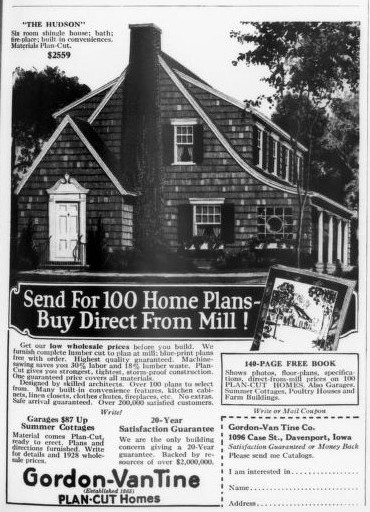

Now brochures, catalogs, advertisements, and newspapers could reach rural homes, as well, creating a consumer culture eager to purchase the latest in personal and household items. While newspapers and magazines were media outlets for kit house companies, most of their advertising was through catalogs mailed directly to consumers or magazines. Lifestyle magazines like The Ladies’ Home Journal and House Beautiful offered visions of the American Dream for homeowners with articles and advertisements on interior design, architecture, cooking, gardening, and other domestic topics. House Beautiful operated an in-house Home Builders’ Service Bureau, as well.

The Arrival of Parcel Post

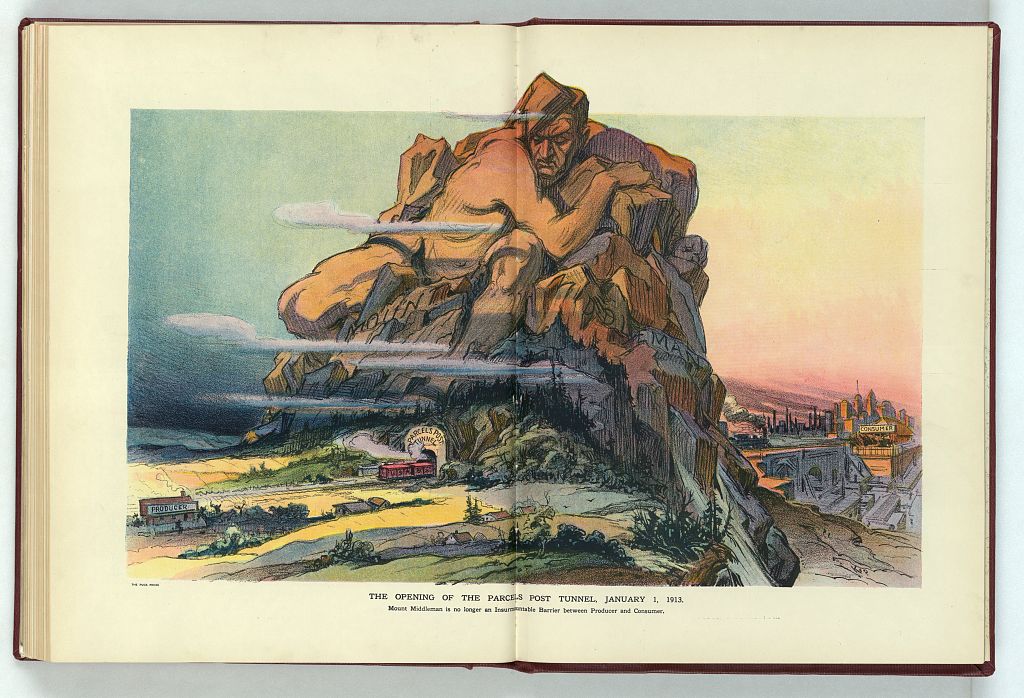

The establishment of Parcel Post in 1913 meant packages large and small could be shipped economically by rail to any community with a railroad depot. Kit house businesses took off.

The Opening of the Parcel Post Tunnel, January 1, 1913. Mount Middleman is no longer an Insurmountable Barrier between Producer and Consumer.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs

The surge in innovation and industry at the turn of the twentieth century created job opportunities filled by an aspirational working class. Accountants, managers, and secretaries were key to the smooth operation of businesses. Increased income meant more money to spend on material goods and leisure activities, hence the growth of service industry employees to meet these needs. These new sectors of the workforce were the customer base for kit house companies.

This growing consumerism helped define “standard of living”—a loose idea of what someone in the middle class should own. The subdivision of large estates and farms opened land to housing development. The growing availability of single-family homes on the outskirts of cities and in new suburbs attracted people eager to transition from renting to owning. Streetcar and commuter rail made it possible to live outside the city, far from urban congestion, yet still commute easily to work. Homeownership became a defining goal of what it meant to be a middle-class family, and kit house companies took advantage of that

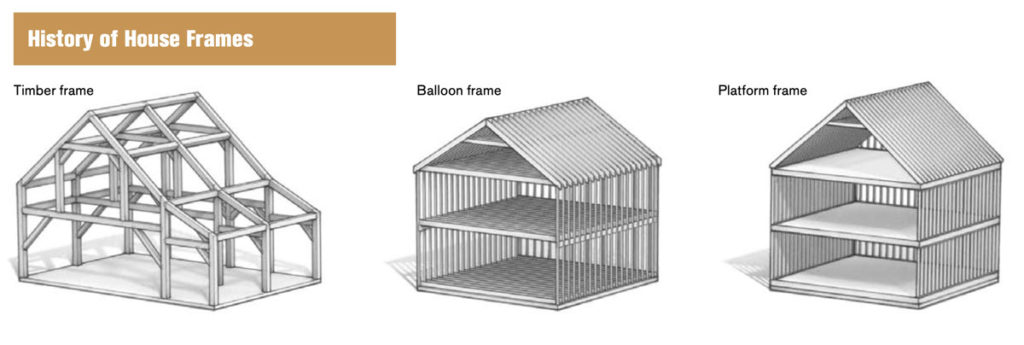

The dizzying array of house models offered by kit house companies was made possible by advances in wood-frame construction. In the mid-nineteenth century, timber frame construction yielded to balloon frame construction, and by the 1930s, platform framing—both of which used dimensional lumber and nails rather than heavy timbers and joinery. This allowed a more complex design with a flexible floor plan and required less skill to erect.

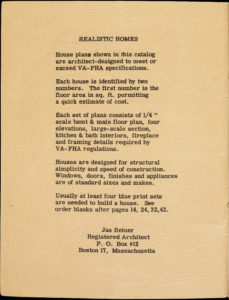

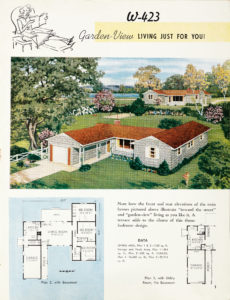

In the early decades of the twentieth century, Tudor, Colonial Revival, and Victorian styles were popular, as well as more modest bungalows, Foursquares, Capes, and cottages. Kit houses offered versions of these styles, often “borrowing” from architect plan books and each other.

To feed consumer hunger for housing, financial institutions began to offer credit backed by Federal Housing Administration (FHA) loan guarantees—placing ownership of a house within reach of average Americans. The establishment of the Federal Housing Administration in 1934 under the New Deal was designed to combat the devastation of the Great Depression by increasing housing stock and home ownership.

Less well known is this program’s role in the so-called white flight from urban areas into surrounding suburbs, leaving African Americans and other minorities in urban centers that were redlined, or designated too high a risk of default to finance. In fact, many developers who used FHA-guaranteed loans created subdivisions that explicitly prohibited minorities. While further research is required, the financing offered by kit house companies prior to the Great Depression may have offered African Americans a path to homeownership that disappeared along with the companies themselves.

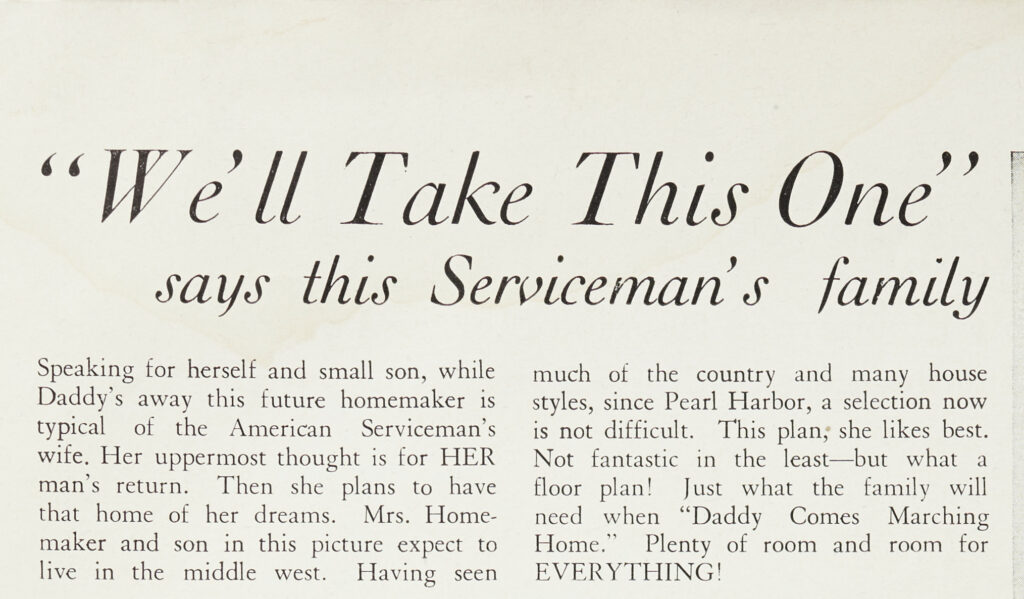

The wide availability of government-backed, low-interest, fixed-rate mortgages through traditional lending institutions, coupled with the surge in demand for housing following World War II, spelled the end of most kit house companies. Typical post-war housing design prioritized function and expedience over character and detail, resulting in the oft-generic styles in large housing developments of the 1940s and 1950s.

Those kit and plan companies that survived, like Aladdin, Bennett, and Standard Homes, kept pace with popular styles such as the Cape Cod, Ranch, and Split-Level and continued to offer personalized service.