Kit Houses

Kit Houses

Burlington, Vermont, and the Kit House Phenomenon

Burlington, Vermont, offers a fascinating case study on the popularity of modest, affordable kit and plan-built houses in the first half of the twentieth century. The growth of a middle class seeking affordable houses, the subdivision of large estates and farms to meet the demand for housing, the expansion of public transportation options, and access to rail lines for delivery to consumers—all these factors were present in the Burlington market. As a result, the city has what is likely a notable concentration of kit houses dating from about 1910 to 1940.

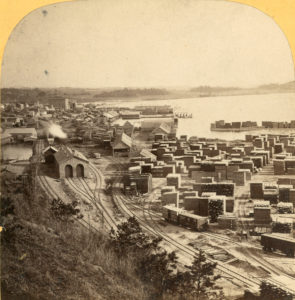

Vermont’s railroad system had been in development for over 70 years prior to the arrival of kit houses. The growing manufacturing industry in Burlington came to rely on this rail network to import raw goods and export finished products; by 1850, goods from Burlington could be shipped as far away as Chicago via a network of trains and boats.

This rail network benefited not only Burlington’s manufacturers but also out-of-state merchants who were now able to bring their own goods into Vermont at a minimal cost. Burlington’s location at the intersection of the Vermont Central Railway and Rutland Railroad would be key to shipping kit houses in the city.

The Growth of a “Middle Class”

The decades leading up to the arrival of kit houses in Burlington were characterized by a growing population and economy. The population of Burlington grew from 18,640 in the 1900 U.S. Census to 27,686 in the 1940 U.S. Census—an increase of 49 percent over 40 years. During this same period, the total taxable wealth in Burlington grew by over one hundred percent, while the per capita wealth grew by less than fifty percent. That the total taxable wealth grew at double the rate of the population and per capita wealth suggests the emergence of Burlington’s middle class.

This period in the city is distinguished by a shift from lumber and textile manufacturing businesses to service and professional occupations. A survey of some of the first kit houses reveals occupants working as dressmakers, carpenters, gardeners, and electricians, as well as physicians and dentists, business managers, and retail owners.

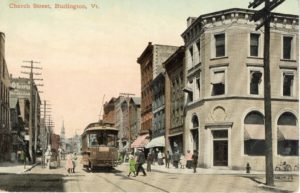

With higher wages, more people were able to buy houses on the outskirts of the city, escaping the congestion and grime while enjoying an easy ride on the streetcar into the city center for work, shopping, and entertainment. By the 1920s, Burlington Traction Company streetcar lines extended along Pine Street, North and South Winooski Avenue, Pearl Street, and North Avenue. Lines that followed Shelburne Street and Flynn Avenue encouraged the development of nearby neighborhoods during this period.

Buy Local

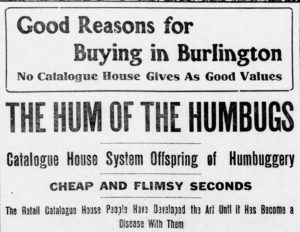

Vermont merchants resisted the arrival of mail-order catalogs in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In September 1901, the Middlebury Register ran an opinion piece decrying women who shopped through mail-order companies rather than at local businesses, claiming they hurt their town more than “half a dozen perpetual cases of smallpox,” bred illness, and were mothers of crime.

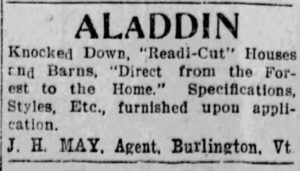

Despite the continued outcry from local merchants, some kit house companies were advertising in Burlington-area newspapers by 1912. Typically, companies used a local real estate agent to market the homes. Of the major kit house companies, Aladdin Homes ads appear most frequently in the local press. Advertising by other kit house companies in local newspapers is rare, confirming that the companies primarily relied on catalogs mailed to households.

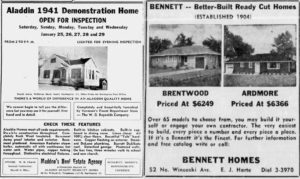

The Great Depression took a toll on Burlington’s economy, and local kit house advertisements became scarce between 1933 and 1940. However, for those companies that survived, 1941 marked a resurgence in demand for housing that accelerated after World War II.

Birchcliff Parkway Development, Burlington, Vermont

Birchcliff Parkway in Burlington was a typical post-war housing development designed to meet FHA guidelines that opened the door to home ownership. The development boasted a convenient location, comprehensive infrastructure, accessible financing, and protective covenants. The reference to a protective covenant in this advertisement requires further research to understand its specific restrictions. Many developments of this period had protective covenants that implicitly or explicitly prohibited minorities.

Burlington Free Press, May 7, 1955