Kit Houses

Kit Houses

Builder's Guides, Plan Books, and Kits Over Time

The nature of kit and plan-built houses has evolved over more than 200 years in concert with changing tastes, socioeconomic conditions, and technological innovation.

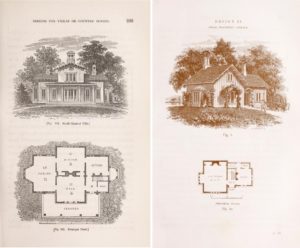

BUILDER’S GUIDES

Early builder’s guides allowed carpenters to supplement their own professional knowledge with instruction on the latest in architectural styles and ornamental details. Asher Benjamin, a carpenter from Greenfield, Massachusetts, is credited with publishing the first manual for American builders, The Country Builder’s Assistant, in 1797. His guides typically featured plates illustrating the Classical orders on columns, balustrades, moldings, door, and window surrounds, and countless other details drawn to scale. Although some guides featured floor plans and elevations, the emphasis was on architectural details. It was through these guidebooks that the popularity of styles like the Greek Revival spread nationwide, even into rural areas. Builders could incorporate details into buildings based on local preferences and affordability.

Early Pattern Books

Pattern books appealed directly to future homeowners with colorful, picturesque renderings of houses in both urban and rural settings. Other than a floor plan and elevations, these books furnished few details, leaving design details to the architect or builder.

Beginning in the 1840s, Andrew Jackson Downing, a horticulturist and architect, published a series of books on rural architecture and landscape design, ushering in a shift from classical architecture to romantic styles like Gothic, Tudor, and Italianate. While early pattern books targeted wealthy families seeking a refuge from the city, they gradually incorporated more modest designs as transportation opened suburban living to the middle class.

Domestic Science and the Modern Home

The popularity of pattern books coincided with the rise of the concept of domestic science, pioneered by educator Catharine Beecher. Her books promoted the importance of the home as the center of moral and physical health. Women became important clients who demanded that a house function efficiently and economically so they could excel as homemakers.

The New Housekeeper’s Manual, 1873, by Catherine E. Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe

Courtesy of University of Maryland

Post-Civil War Plan Books

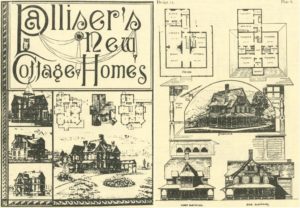

In the late nineteenth century, architects jumped on the plan book wagon in droves, bringing the pattern book concept a step closer to the mail-order house kit. Bridgeport, Connecticut, architect George Palliser’s first catalog, Model Homes for the People, A Complete Guide to the Proper and Economical Erection of Buildings (1876), featured a floor plan, specifications for all details, an illustration of each home, along with a brief description of the features of the house and an estimate of the cost to build.

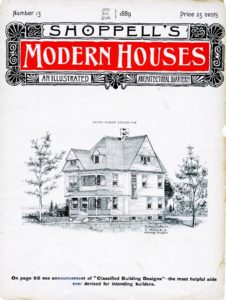

Through his Cooperative Building Plan Association, Robert W. Shoppell produced a competing line of catalogs, beginning with Artistic Modern Homes of Low Cost in 1881, as well as home-building guides and a magazine. Shoppell also publicized his designs in periodicals, an inexpensive way to expand his market that proved highly profitable. Both Shoppell’s and Palliser’s catalogs featured advertisements for building materials in the rear pages, providing a ready resource for home builders.

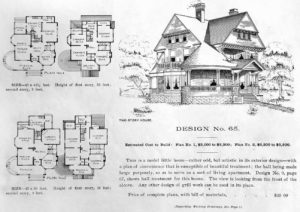

A PLAN PLUS

Emulating George Palliser’s mail-order plan concept, Knoxville, Tennessee, architect George F. Barber produced the Cottage Souvenir catalog series beginning in 1887. Barber’s catalogs included price lists and order forms for plans, an estimate of the cost of materials, and sometimes featured a photograph of a completed house. Over two decades, Barber’s firm of thirty draftsmen produced more than 800 designs and sold about 20,000 sets of plans. There is some evidence that the company occasionally crated and shipped construction materials and other elements like staircases, windows, and doors to the site—a harbinger of the kit house phenomenon to come. Barber’s clients represented the growing middle class that would patronize the kit house companies in the early 1900s.

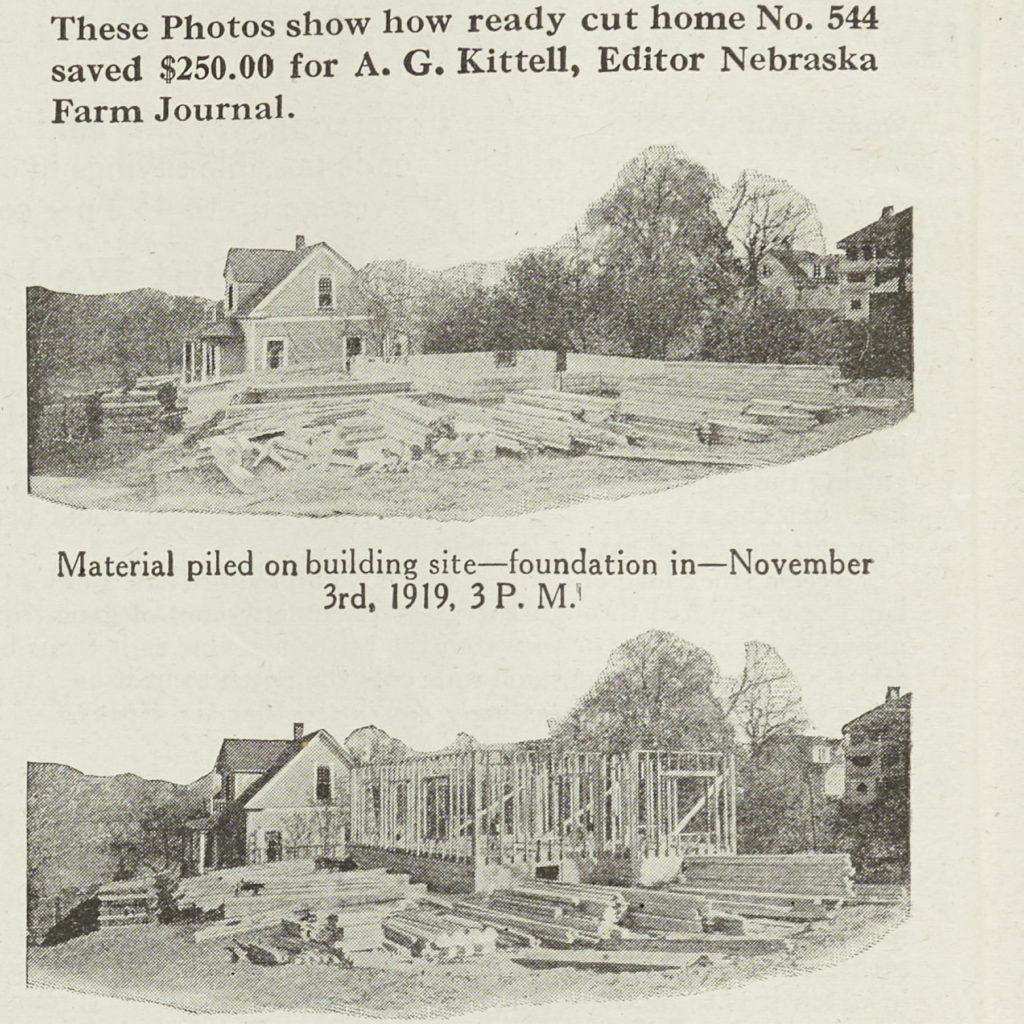

MAIL-ORDER KIT HOUSES

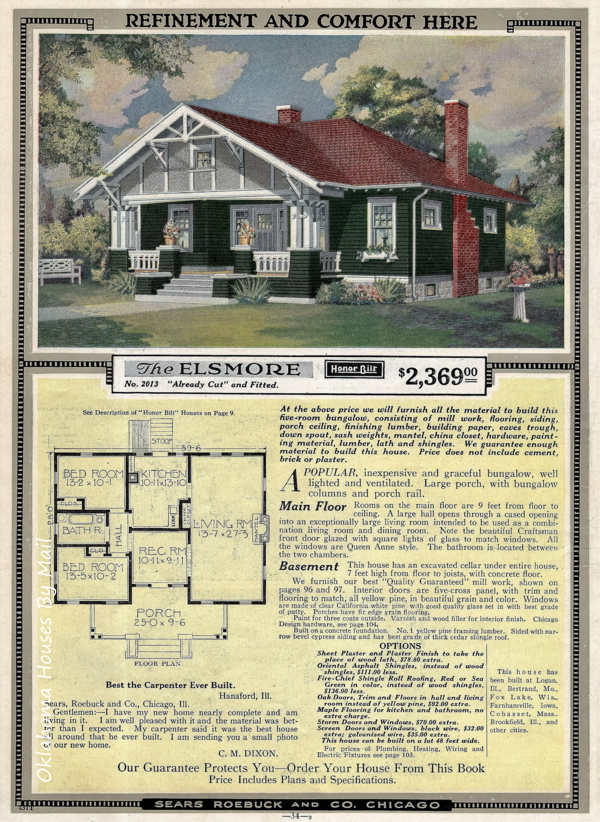

In the early 1900s, kit house companies took customer service a step further by providing home buyers with, quite literally, a complete house in a boxcar. Building materials traveled by rail to the nearest train station and then to the building site by truck. A local builder or the owner assembled the house, using materials and instructions provided. In contrast to handbooks of the previous century, which catered to the upper class, these catalogs marketed an economical, efficient, and customizable suburban ideal to the middle class, especially women. To attract customers, many kit house companies provided financing with favorable rates. Bungalows and Foursquares were the most popular styles.

POST-WAR PREFABRICATED HOUSING

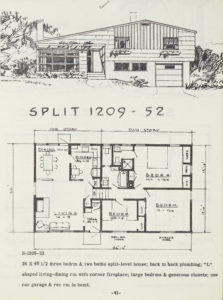

The industrial advances of the World Wars, combined with the intense demand for housing following World War II, triggered the development of fully prefabricated homes in the 1950s and 1960s. In contrast to kit houses, these were constructed in three-dimensional sections, or modules, at a factory and then transported to the site for quick assembly. Plan books depicting the Capes, Ranch houses, and Split Levels popular at the time were produced by companies like the National Plan Service and Realistic Homes. Lumber, roofing, masonry, and other materials suppliers distributed these plan books under their own names to customers.

Lenders were more willing to provide affordable mortgages, thanks to the Federal Housing Authority (FHA), established as part of the New Deal. The FHA insured mortgages made by private lenders for single and multi-family housing. After frugal living during the war years, couples were eager to begin a family and build a future—and home ownership was central to that dream.

EMERGING TRENDS: TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY MODULAR HOUSES

Technology, culture, and economics continue to shape the small house of the twenty-first century. Modular construction, which acquired a reputation for bland sameness during the building boom of the mid-twentieth century, today is applied to high-end, architect-designed homes as well as more modest homes. Like their predecessors, modular house companies promise customers savings in time, money, and newly important today, energy efficiency.

EMERGING TRENDS: TINY HOUSES

Closer perhaps to the mobile home in function and form, the tiny house responds to a wide range of buyer motivations—physical and financial freedom, affordability, sustainability, and simplicity. Today, a home buyer can purchase a tiny home on the Internet from retailers like IKEA and Home Depot, much as buyers ordered from catalogs in the twentieth century.

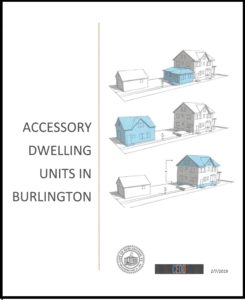

ACCESSORY DWELLING UNITS

Affordable housing is a critical concern across the country, and many cities permit Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) as part of the solution. In Burlington, Vermont, city leaders have loosened rules on ADUs, defined as self-contained, independent housing units within or on the same property as a single-family, owner-occupied house, to address the housing crunch. Easy to assemble modular houses and tiny house-style buildings may be among the options.